Seattle, a coffee haven, is watching java prices spike. Why?

Published in Business News

SEATTLE — How much does that morning cup of joe cost? The price may give you a jolt.

The price of a coffee is no longer under, like, $5," said Emma Ueda, 27, who lives in Seattle. "It could be a $12 day, just going to a cafe."

As the hometown of Starbucks and countless coffee shops, Seattle lives up to its reputation as a city that holds java in high regard. But, recently, coffee prices have been on the rise, brewing trouble for businesses, which are already struggling with bitter conditions and cost-sensitive customers.

The American price tag for jitter juice surged about 20% in August year over year, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

The swell is driven by an ongoing supply chain crunch worsened by shortages of raw coffee beans around the world. This year, President Donald Trump's tariffs also brought another costly challenge for a market that imports 99% of its product, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

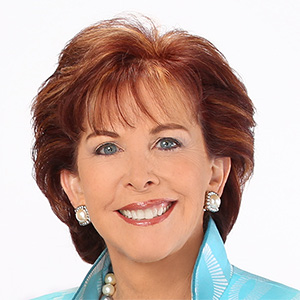

Navigating these stumbling blocks has forced coffee purveyors to learn “to be agile,” said Peter Mark Ingalls, owner of Seattle-based coffee roaster Kuma Coffee.

“We have to raise a bit here, but I don’t want to burn people or kind of add to the problem,” he said.

Consumers are adjusting their habits to keep up with the changing market.

Vanesa Carrillo Navarrete, a 24-year-old Seattleite, carries small bottles of sugar-free vanilla and caramel syrups with her to cut costs when she buys lattes.

Coffee is "a big part of the Seattle culture, and I don't want to give it up entirely," she said. "It used to be an everyday ritual, for me at least, but, with these prices really climbing up, I take a double take."

'Record high'

American demand for coffee is strong. Adults in the U.S. drink around 490 million cups of coffee on a daily basis, according to the National Coffee Association, the industry's trade group.

To meet the nationwide need for caffeine, much of the supply has to be imported.

The U.S. Agriculture Department’s Economic Research Service said the country purchased about 80% of its unroasted coffee in 2023 from Latin America, with 35% from Brazil and 27% from Colombia. That largely falls in line with major sources of global production.

Brazil reigns supreme as the world's top coffee producer, with the South American nation accounting for 37% of 2024-25 global production, according to the USDA's Foreign Agricultural Service.

Comparatively, the U.S. ranks No. 38 in coffee production. Tropical climates are ideal for growing coffee, so only Hawai‘i, Puerto Rico and California are suitable for domestic production.

Increased demand worldwide, combined with smaller coffee harvests in recent years, are affecting coffee prices, the National Coffee Association said. Reduced yields are tied in part to weather conditions like droughts and frosts.

Trump’s deluge of tariffs is hitting major coffee exporters, particularly Brazil, which has been rocked by a 50% duty.

"It’s difficult to predict exactly how much tariffs will impact consumers’ pocketbooks, but coffee prices are already at record highs due to a number of supply and demand factors, and further significant increases would be expected the longer tariffs remain on everything from coffee to packaging and roasting equipment," said William Murray, the National Coffee Association's president and CEO, in a statement.

Some relief could be on the way, after Trump issued an executive order earlier this month detailing that tariffs on products that can't be "naturally produced in sufficient quantities in the United States to satisfy domestic demand" could be modified in the future.

'It's a mess'

Local businesses are taking different approaches to the headwinds. But some are better positioned than others.

Coffee giant Starbucks is keeping its eyes on market fluctuations.

“Both the tariff environment and coffee prices continue to be dynamic," said Chief Financial Officer Cathy Smith in the company's latest quarterly earnings call.

A Starbucks spokesperson said Wednesday that the company has a history of successfully navigating global changes, and it continues to monitor potential impacts to its business.

It sources its coffee from more than 450,000 farmers in 30 global markets, including Brazil, and its coffee purchasing practices help reduce price volatility and ensure a healthy supply of green coffee, or raw coffee beans, the spokesperson said.

Emanuele Bizzarri, co-owner of Caffè Umbria, has worked in the coffee business since the 1980s. With prices hitting unprecedented levels on the C market, otherwise known as the coffee futures market, Bizzarri said he's never seen anything like this.

"We're at a historical high," he said, while adding that there's a lot more demand, too. Despite the hurdles, his company is growing, particularly on the wholesale side.

Seattle-based Caffè Umbria has expanded across the country. In addition to its four cafes in the Seattle area, it has three in Portland, two in Chicago and one in Miami. Bizzarri said the company serves coffee that's blended from different foreign varieties, and it mainly imports from Brazil, Colombia, Guatemala, Kenya and Papua New Guinea.

Bizzarri said the most significant changes hit the industry after the COVID pandemic.

He described present-day shipping as a "nightmare," with congestion, delays and a dearth of food-grade containers.

Then, there are the tariffs. Bizzarri explained that contracts are often set a year or two in advance — and, now, they're subject to changing duties.

"Your costs are completely different than what you thought your costs were," he said. "It's hard to budget."

While the Trump administration's tariffs on most coffee-producing countries range from 10% to 25%, the 50% tariff on Brazil is especially hurtful to coffee purveyors, Bizzarri said.

The company's importer sends him the bill from the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, and "it's a big chunk of money," Bizzarri said.

On top of that, he added, the coffee industry is feeling the squeeze from weather events, such as reports of frost in Brazil.

Caffè Umbria raised prices earlier this year, Bizzarri said, but it didn’t implement dramatic spikes.

"If we would pass everything (on to customers) that we got increased right now, you would have a caffè latte that's going to be over $20," he said. "Nobody's going to buy that."

His conclusion: "Not a good time to be in the coffee business right now. ... It's a mess."

Meanwhile, Ingalls' business differs from others in his industry because he doesn't run a cafe, but instead focuses on wholesale and selling directly to consumers.

He travels to other countries to import coffee from farms, co-ops and mills. Ingalls largely imports from Guatemala, Colombia, Mexico, Honduras, Kenya and Ethiopia.

He said that Ethiopian and Peruvian coffees are slightly more affordable this year.

The fair-trade minimum price for conventional Arabica coffee is around $2 per pound, according to nonprofit Fairtrade International.

Kuma Coffee shells out $3.50 to $4 per pound, based on Ingalls' argument that paying small farms a lot for high-quality crops is the best path forward to creating better conditions for foreign producers, their communities and economies.

However, "coffee costs are going way up," Ingalls said. The price for a satisfactory blended coffee has jumped to almost $6 per pound, he added.

Ingalls blames several factors. For starters, coffee yields from Central American countries and Vietnam are down, so there's less to buy, he said.

"There's not much around, so everything costs a lot more that is available," Ingalls added.

He's also feeling the pressure of the 50% tariff on Brazil. He described Brazilian coffee as an international favorite because of its sweet, nutty, chocolate-tasting flavor that complements milk.

"Across the board, from big to small roasters, everybody uses Brazilian coffee," Ingalls said. "That's like the world's house espresso."

Tariffs, he said, are "clearly a negotiating tactic, but, in real time, they're impacting us, and we have to send it on to the consumer — at least, in some part."

'Better than Uber'

In Seattle, business owners in the coffee industry have to contend with the city’s high operation costs.

Here, "real estate is very expensive, so everybody has to pay a lot for rent," Ingalls said. "Labor is super expensive, with minimum wage going up and then the tips rules changing."

He's figuring out how much his business can absorb financially and how much to pass on to his patrons.

As a consumer, "I'm having sticker shock," Ingalls said, and he doesn't want to worsen the problem.

Mehmet Gultekin, owner of The Seattle Grind, arrived in Washington from Turkey about two years ago and opened his Uptown coffee shop soon after.

In the city, "taxes are so high," Gultekin said in a phone interview. "Coffee shop owners have huge fees."

He considers Seattle's minimum wage to be steep — "and it will be going up, I'm sure."

But he believes a few elements fall in his favor.

Gultekin depicts his shop as similar to a kiosk, so his rent is cheaper than the standard. Though he employs two part-time workers in the summer and one in the winter, Gultekin also mans his own shop.

He caters to tourists during the warmer months and employees of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the Space Needle and Seattle Center in the winter.

Compared with other coffee purveyors, Gultekin keeps his prices low — hovering in the $5 to $6 range.

It's "still expensive" to run a coffee shop in Seattle, Gultekin said. But he prefers the coffee industry to other options.

"Better than Uber, Gultekin said.

©2025 The Seattle Times. Visit seattletimes.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments