Loud TV commercials drive viewers crazy. California wants to quiet them down

Published in Business News

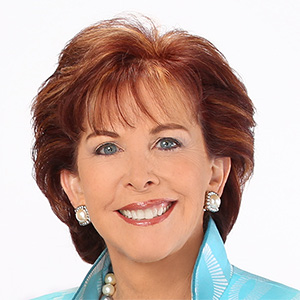

Richael Keller has always been sensitive to loud commercials, but when thundering streaming-service ads disturbed her sleeping newborn, her reaction was heated enough to blaze a path to the California state Capitol.

Keller’s husband is Zach Keller, legislative director for Sen. Tom Umberg, D-Santa Ana. Last year, when the pair became new — and newly exhausted — parents, their reprieve was watching a TV show on a streaming service while their daughter napped. Even though the TV and the baby were in separate rooms, a random commercial would “blare so loudly that it would startle (the baby) and wake her up,” Keller told The Times.

Keller said her husband was long aware of the issue, but it had now degraded the quality of their lives to the point that he was spurred to act.

Keller’s boss, Umberg, authored Senate Bill 576 to lower the volume on commercial advertisements, which passed the Legislature and now awaits the governor’s signature.

If approved, the legislation would prohibit streaming services including Hulu, Netflix and Prime Video from playing commercials louder than the shows and films they offer on their platforms.

For the bill to become law, Newsom has until Oct. 12 to sign it.

How can platforms control advertisement volume?

In short, they can’t. At least not directly.

But regulators can notice when there is a pattern of consumer complaints and then investigate further for possible enforcement.

That’s the approach the Federal Communications Commission has taken with laws regulating advertising volume already on the books.

The Commercial Advertisement Loudness Mitigation (CALM) Act requires broadcast, satellite and cable TV providers to ensure that commercials aren’t louder than the programming they are accompanying, but it does not include streaming services.

Under the law, advertisers must match the average loudness of the surrounding program, which is measured by a standardized algorithm and enforced by networks through automated checks, said Jura Liaukonyte, professor of marketing and applied economics at Cornell University.

“Because the law governs the average, some moments in a spot can be much louder as long as the ... average stays within tolerance,”Liaukonyte said.

That’s just enough wiggle room for sound engineers, who can try tricks of the trade to make commercials feel punchier and be perceived as louder while staying within the rules, Liaukonyte said.

“So, the automatic checks show compliance, but to viewers the ad still comes across as louder and more aggressive than the program,” she said.

The CALM Act was signed into law by President Obama in 2010 and is enforced by the FCC. In the years after it went into effect, the agency said complaints about commercial volume dropped significantly.

The agency relies on consumer complaints to monitor industry compliance.

Even though consumer complaints plummeted, the FCC said in recent years the commission had received thousands of complaints from viewers who remained “frustrated by the loudness of television commercials.”

“The high number of complaints took a troubling jump last year, which warrants a second look,” the FCC stated in a news release.

In response, the FCC adopted a Notice of Proposed Rulemaking that allowed the commission to put out a call for consumer feedback on the CALM Act’s effectiveness in controlling and preventing exceedingly loud commercials; the feedback request expired April 10.

When the agency looked at the responses, many of those complaints led back to streaming services. Now, the agency is considering if it should expand its enforcement capabilities.

What’s the streaming industry’s stance?

In a four-page letter against the bill, the Motion Picture Assn. and the Streaming Innovation Alliance, which represent streaming services including Disney and Netflix, initially opposed the bill, saying they don’t have the ability to control volume settings on all devices in which their content is offered, reported Politico.

They argued that unlike the situation with broadcast and cable TV providers, where ads are sold directly to networks, on their platforms “streaming ads come from several different sources and cannot necessarily or practically be controlled,” Melissa Patack, the MPA’s vice president of state government affairs, told lawmakers in June.

But the group has since changed its stance after the bill was amended with a legal provision that won’t allow individuals or private parties to sue streaming services for violating the law.

As a result of the amendment, both groups are neutral on the bill, a representative told The Times.

_____

©2025 Los Angeles Times. Visit at latimes.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments