'Do I need it?' Groceries cost 20% to 40% more than before the pandemic. How San Diegans are making do

Published in Business News

SAN DIEGO — Mike Portal uses a no-fee credit card that gives 6% back on groceries. He pays it off every month.

The chicken drumsticks in Chris Lovelace’s freezer cost 99 cents a pound, far cheaper than the red meat he used to buy.

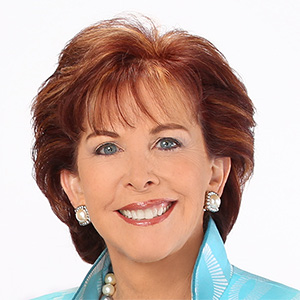

Margi Thornburgh, a night owl, checks ads and clips coupons every Wednesday at midnight and hunts for more discounts on store shelves.

“I really get a thrill out of getting a bargain,” she said after spotting $1.99 smoothies at Vons recently, down from $3.99. Because they were half off, she bought 12 instead of six. “I was skipping out of the store with a big smile on my face.”

These are some of San Diego’s super shoppers, who have been training for this era of fast rising grocery prices for decades.

Some have the resources to turn frugal shopping into a sport of sorts — a car that lets them buy in bulk, time to shop for deals, storage space, multiple grocery stores close to home. For others, strapped for space or time, the path to eating adequately while not overspending is more challenging.

Grocery prices have risen for a mix of reasons, including pandemic-era supply chain blockages and import tariffs that are passed on to shoppers.

In San Diego County, food eaten outside of restaurants cost 4.4% more this July than a year earlier. That is the latest figure from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, whose publications stopped due to the federal shutdown.

Fresher data — St. Louis Federal Reserve Bank’s nationwide FRED figures for September — show milk prices were up 10 cents a gallon over last year and up 68 cents over five years earlier, a rise of almost 20%. White bread was down 11 cents from last year but up 38 cents from five years earlier, about 25% higher. Ground beef cost $6.32 a pound, up from $5.67 a year ago and $4.08 in 2020.

In the San Diego metro area, meat was 41% higher last month than in October 2019, dairy was 27% higher and produce was 18% higher, according to a grocery price index by Datasembly, a market analytics company that tracks prices of 1,000 products weekly across the United States. Local prices of meat and non-alcoholic beverages kept rising in the past six months, produce is almost even, and dairy and bakery items have fallen slightly, Datasembly found.

Faced with these higher prices, San Diegans have changed how they plan and eat.

They are abandoning foods and replacing stores they shopped at for decades with ones that have sales and coupons. They’re clinging to a few favorite items — Diet Coke, Diet Snapple, eggs and bourbon were mentioned. But they’re giving up a degree of control, opting to eat what’s on sale and not what they’re craving.

They’re doing the math: if I spend this much on gas to drive around or spring for a freezer, but I save that much on food, is it worth it?

Trading time for money

As a teenager, Thornburgh learned to write grocery lists and shop weekly sales. Some 50 years later, she still uses those methods. But as local food prices have risen, outpacing the national inflation rate, Thornburgh has taken things further, combining every strategy she can think of so she doesn’t spend more than she must.

“I look at all the ads either through the emails I receive or directly on the apps. I make my list by store of which items that I want to purchase. … I’m able to shop at multiple stores in one trip. I always bring a cooler to store cold and frozen items,” she outlined in an email to The San Diego Union-Tribune.

Strolling through aisles, she keeps looking for deals.

“I can be in a store, see an item on the shelf, and I will pull up the Target app, the Walmart app, the Food 4 Less app,” she said. “Any app of the store that I’m not in. And I will look for the price … and I will say, ‘Am I going to buy this here or am I going to go to another store?’”

Her weekly grocery loop is time intensive, taking 90 minutes to two hours and covering as much as seven miles. Stops include Walmart, Food 4 less, Trader Joe’s and Vons. She recently folded in Aldi, drawn by an ad for 55-cent avocados. She picked those up, plus raspberries and asparagus, all on sale.

Thornburgh, 70, gets income from contract sewing and Social Security. She is not among the 53% of adults who, according to a poll by AP-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research, see grocery expenses as a “major source of stress.” (Groceries beat housing and health care costs and having inadequate savings or income as the top financial worry.)

“I feel that I’m skilled enough and take advantage of all the tools out there,” she said. “I don’t feel stressed. But I’m very conscientious.” She reminds her husband: “If it’s not on sale, I’m not buying it. So he was really happy this week when Ding Dongs were on sale.”

With these efforts, she spends around $100 a week, up from $60 before the pandemic, and saves around 50% on average at Vons and 40% at Food 4 Less.

“With the money I save, it’s worth the investment of time,” she said.

Thornburgh offered one more hint: don’t just shop online. Go inside stores. She acknowledged that shopping online and picking up groceries is convenient for some people, including parents of young children, but “you will miss the in-store sales, and sometimes those are substantial.”

More salad, less red meat

Jeff Lonsdale, Ken Sobel and Chris Lovelace are cutting back on red meat.

“I don’t buy steaks anymore,” said Lonsdale, 68, who lives in a mobile retirement community in Oceanside. A half-package of sirloin burgers from Costco has been sitting in his freezer because he has “better, more affordable choices” today.

He used to buy what he wanted, but as his income as a contract circuit designer fell and food prices hit new highs — especially for the beef burgers, steaks and pork chops he once enjoyed — he has changed his habits.

“It used to be: I want it, I’ll go get it. Now I think, do I need it? Then maybe I go get it,” he said. “I don’t need doughnuts and cakes and desserts and that kind of thing, so I don’t even bother.”

Currently, he said, “my income is short of expenses each month. My savings account keeps me above water.”

Worried about cash flow, Lonsdale started tracking all food spending this year — both at stores and the occasional trip to Taco Bell. All together, his monthly spending on food is around $65 this year, he said.

A food rescue program he visits three times a week helps him hold down costs, bringing surplus items from local grocery stores to his community. Around 40 people visit each time, he estimated.

One recent morning, he picked up seafood salad with crackers, a 12-ounce watermelon cup, two mesquite-seasoned pork chops that totaled 12 ounces, an Earthbound Farms brand veggie tray with ranch dip, baby carrots, broccoli and celery, a Nathan’s hot dog and a 6-ounce Caesar salad. Based on the price tags he saw, he said the total might be around $20.

“I mean, would you spend $3.99 for a little tray of cut up watermelon?” he said. “I get it for free and I’m loving it. And it’s not just the volume. It’s the variety. Things I have never thought about trying, never knew they had, wouldn’t have looked for.”

Another nice surprise: goat cheese with herbs. “Wow, I’ll try that. It’s free. It was good.”

Sobel, 71, who lives in La Jolla, cut out most meat and some other high-cost grocery items.

“Sticker shock was a huge part of it — the prices that went higher all the time and the quality going down, almost commensurately,” he said. “That brought my focus back into buying only healthy foods, buying only what I’m going to eat, being careful about our choices.”

After a hospitalization, Sobel decided to lose weight. He changed his diet in June and stopped buying “a lot of the high-price, mass-produced snack foods … that have skyrocketed in price.”

One more change: “I really don’t throw away food anymore.” He makes a chef salad using turkey breast or sliced ham and eats that several days in a row, “until it’s completely gone.”

“I’m lucky enough to be able to cut about 40% from my food budget and afford to eat,” added Sobel, who reduced his household’s average monthly grocery bill from around $550 (not counting the occasional restaurant delivery) before June to around $400 now. “But what about kids and seniors and low-income families who are losing their SNAP benefits?”

Almost 400,000 San Diego County residents saw their CalFresh benefits — the state’s version of the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) — halted Nov. 1 amid a federal government shutdown, now in its sixth week. Federal judges later ordered that funds be restarted.

Between workers whose pay was frozen by the federal shutdown and people whose food benefits were postponed or trimmed, demand is surging at food banks and food-rescue nonprofits, whether in small communities like Lonsdale’s or at large distribution centers.

Trading space for savings

In Encinitas, Lovelace rarely buys red meat at the store anymore. Instead, he goes out for quality burgers. “It’s got really, really good meat,” he said of Versailles Cafe’s $18 cheeseburger and fries. “It’s a real half pound, not a seven ouncer.”

Lovelace’s rooftop solar on the house he and his wife, Dana, bought almost 50 years ago powers the two chest freezers he keeps in his garage.

“I still don’t have any chicken breast in my freezer that I paid over $2 a pound for,” he said. Bacon was purchased at $4 a pound — around half of what it costs now full price. He is still working through the dozen packages of breakfast sausage he bought at half-off a while back.

When he shops, he buys enough meat to last until the next big sale.

Lovelace, who is 75 and retired, stopped shopping at stores that don’t send weekly ads. Like Thornburgh, he lives in a grocery-dense neighborhood with “all the big chains, so it’s really easy to get to places.”

He focuses on house brands over pricier, name-brand versions. In-season food is also cheaper, he added. And he knows the market.

“You have to know your prices. Sometimes that good deal really isn’t,” he said.

These efforts are keeping the couple’s grocery costs almost even with last year: $560 a month in 2023 and 2024 and $577 this year, on average.

“Doubtless expenses will begin to rise this holiday season as we liquidate our older inventories but we’ll still be kicking butt on money spent for food compared to any of my friends or neighbors when we compare notes on this topic,” Lovelace wrote in an email. He also credited his wife, who embraces his “cheapo philosophy.”

In Mt. Helix, Portal is back to shopping like he did when he was a newlywed in the early 1990s — only now he has that cash-back credit card.

“I was in the beginning of my career,” he said of his frugal youth. “We chose to have my wife stay home and take care of the babies. So, yeah, we pinched pennies and cut corners to save money.”

Now his kids have kids and Portal, 65, has a home on Mt. Helix and a mortgage consulting business. But with the “tremendous increase in food costs” he has observed this year, he buys food on sale and stopped shopping at Whole Foods. “It’s just too high.”

His small freezer holds berries bought on sale, which his toddler grandchildren devour. He also buys discounted meat and uses a vacuum sealer to avoid freezer burn. Ribeye on sale rose from $6 a pound to $9 or more, but even that is a relative bargain compared to full price, he said.

Uncooked beef steaks cost on average $10.88 a pound last September and $12.26 this September, up from $8.13 five years ago, according to St. Louis Fed FRED data.

To keep grocery expenses roughly the same as last year, even while springing for steak — and the chicken he cooks for RiRi, his 13-year-old Labrador pitbull mix — Portal and his wife stock up ahead of big holidays, when sales are “the best.”

He gushed about his credit card, an American Express Blue Cash Everyday Card. Never carrying a balance is key, he said.

Portal pointed value hunters to GTM Discount General Store, a surplus seller whose weekly sale recently featured 50% off Eddie Bauer sweatshirts, 40% off flood lightbulbs and 40% off spring wreaths. It has great deals on food, Portal added.

Lovelace said he’s lucky to have two freezers and the garage shelves he built himself. “We have places to put stuff, and some people don’t. A lot of the things we do don’t apply across the board.”

But his approach of stocking up when prices drop has worked across his lifetime.

“In any given era, the same rule applies: prices on food have not gone down realistically over any real period of time in my lifetime. Little dips down and big jumps up,” he said.

©2025 The San Diego Union-Tribune. Visit sandiegouniontribune.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments