This anthropologist traveled America to explore our dividedness. Here's what he found

Published in Books News

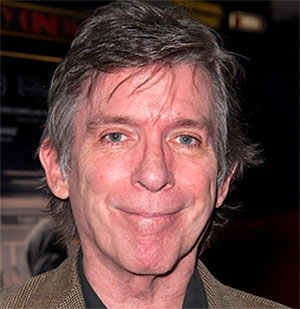

When Donald Trump won the presidency in 2016. Anand Pandian knew almost no one who had voted for him. He had a hard time grasping what the result meant about the country he grew up in.

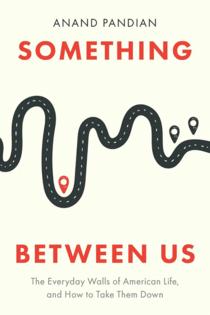

That election became the springboard for a sprawling project by the Johns Hopkins anthropologist. Pandian’s new book, “Something Between Us: The Everyday Walls of American Life, and How to Take Them Down” chronicles the eight years he spent crisscrossing the United States, meeting hundreds of people of varying beliefs and occupations in places ranging from Las Vegas to Hoosick Falls, New York, from Fargo, North Dakota, to Denton, Texas, trying to knit together a sense of what it means to be an American in 2025.

What the author, the son of Indian immigrants, found was a nation in which dividedness is embedded into the very landscape we share, from the walled-off, isolated homes Americans prefer today to the increasingly huge and self-protecting vehicles they drive. He believes the trends only harden the “walls of the mind,” keeping the culture sadly divided.

“Something Between Us” also explores how such walls might be brought down, and Pandian finds hope in the many people he met who work hard to promote a “culture of collective caretaking.” He discussed these dynamics in an interview with The Baltimore Sun. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

An eight-year project is a huge undertaking. What inspired it?

As an anthropologist, I’m trained to try to make sense of people’s lives in different societies, why people do the things they do, why they want what they want, and how they imagine what it means to lead a good or meaningful life…I began to feel that I should make use of some of those skills to try to make sense of how we got here as a country, and in particular to try to make sense of the deep social division and the appeal of a national politics that, to me, felt deeply xenophobic and deeply exclusionary and raised fundamental questions about who truly belongs in the United States.

You wrote that Americans share a common land but that “everyday infrastructures of defense and retreat” help separate us from each other. Can you explain?

It’s curious and interesting, but also troubling, to see all the ways in which the value of being able to cocoon yourself in a space of your own infiltrates so many dimensions of contemporary American life. It’s one thing to think about this with regard to the suburbanization of our homes, the increasing size of these domestic spaces that people occupy in this country, [or] the distance between people in the layout of neighborhoods.

Then, when you begin to think about it … at other levels, you begin to see certain patterns. How do we explain the fact that the American automotive market is so thoroughly dominated now by massive vehicles, by SUVs and trucks that now represent [nearly] 80% of the domestic auto market in a way that’s completely unlike any other country? How did we get to the point where the most desirable vehicle is one that looks like a brick but still moves at impossibly fast speeds? It’s [important] to think about what effects that might have on others who occupy those streets.

You went out of your way to converse with people whose views differ from yours, including one arch-conservative you texted and debated with for years. How did that go?

What I’ve learned … is that you may have very little in common with them, they may hold to things that you find objectionable, and yet you might still be able to have a conversation. You can connect with people. If there’s any hope I hold out for the future of this country, it has to do with what remains possible in those more unexpected forms of encounter.

I think about an older gentleman that I sat next to on a park bench in a town in southern Michigan, a retired factory worker who …wound up telling me about all kinds of worries that he had, about his own economic situation, his wife’s medical condition, and telling me that he had just voted for Trump. Then he said that even though he didn’t know me from Adam, he felt that he owed something to me as a newcomer to his town, that whether I was brown or Black or red, as someone who had showed up in his town, he had to look out for me, and he scrawled his name and number on a piece of paper and passed it over to me. Things like this kept happening in unexpected ways.

They’re really minor moments, but they still tell me that what’s happening on the ground in our country, in the ground-level reality of our social and political life, is more complicated than the political or electoral map may lead us to believe.

In your travels, you visited and spoke with Somali immigrants in Fargo, North Dakota, automotive designers in Los Angeles, gender equality activists in Ohio, and home builders in Orlando. You spent a day among white nationalists in Tennessee. But you return in the last chapter to Baltimore, a city that reflects both sides of our cultural divide.

I’ve lived in Baltimore for close to two decades now. It feels like home in a way that no other place really does … [My family and I] are lucky to live in a neighborhood in which there is a great deal of neighborliness, a neighborhood with a front-porch culture, where people are using sidewalks and talking to strangers on an everyday basis, in a really meaningful and important way.

On the other hand, it’s true that this is also the city that pioneered residential segregation by race in the United States. It is a city where the reality of stark racial inequality remains such an organizing force in the everyday circumstances of people’s lives. That reality came home to our family in a really difficult way in the weeks after that election in 2016 when our son came out of the locker room at [a local swimming pool] in tears at the age of eight saying that he had just been taunted for the color of his skin, saying that kids were in there, older kids, teenagers, that had been talking really loudly about how much better the facility was when they didn’t allow “coloreds” inside.

This was really painful, but it was a reminder that those realities remain with us.

But at the same time, there are people who are organizing against those realities in important and meaningful ways. Part of what I also talk about in the book are movements for environmental justice that I’ve been privileged to take part in in this city, that have to do with the history of the environmental dimension of racial discrimination here … If a book like this does end on a hopeful note, it has a lot to do with the fact that I begin and end in Baltimore, in the company of people who model on a daily basis the possibility of living with a meaningful commitment to justice, equality and the possibility of an everyday life that is livable for all of us.

There’s a lot of work of that kind that’s being done in this city and elsewhere across the country. I draw a great deal of inspiration from that.

©2025 The Baltimore Sun. Visit at baltimoresun.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments