Andreas Kluth: If Rubio is America's superego, Stephen Miller is the id

Published in Op Eds

The American attack on Venezuela to snatch-and-grab its dictator was many things: militarily masterful, legally cynical, strategically and morally warped, and entirely uncertain in its ultimate outcome for Venezuela, the Western Hemisphere and the world. It also was and is devastatingly revealing about the foreign-policy apparatus of this White House.

At the top, of course, is President Donald Trump, who makes his decisions based on caprice and ego rather than strategy or principle.

Having spent years lambasting his predecessors for “intervening in complex societies that they did not even understand,” such as Iraq and Afghanistan, he has now decided — possibly spontaneously during a press conference — that the U.S. should “run” Venezuela.

Having pretended that his campaign is a “war” of self-defense against drugs (even as he pardoned another former Latin American head of state who was doing time for narco-trafficking), he now talks mainly about the oil to be extracted from the supine nation.

Having called the dictator he snatched, Nicolas Maduro, “illegitimate,” he has now thrown the presumably legitimate, meaning democratic, opposition leader under the bus, calling her a “nice lady” who lacks respect. (That nice lady, Maria Corina Machado, recently won the Nobel Peace Prize which he coveted.) Trump now seems content to run Venezuela with the help of satraps from the same illegitimate regime that he just decapitated.

Contradictions, contradictions. But in one sense, Trump is consistent and honest. In worldview and instinct, he is 100% might-makes-right and imperialist. He wants to dominate, if not subjugate, the Western Hemisphere, which is why he has already renewed threats against Cuba, Colombia, Mexico and even Greenland, which is owned by one of America’s oldest and truest allies, Denmark. He’s also increasingly clear that asserting this “Donroe” sphere of influence behooves him to let Russia’s Vladimir Putin and China’s Xi Jinping do the equivalent in Europe and Asia.

Where does that leave the rest of his administration? That depends on the individual, and whether he or she is up or down, in or out, scrupulous or ambitious, one-dimensional or sophisticated.

Among the minor characters, Tulsi Gabbard has in effect become invisible. She’s nominally the director of national intelligence (who in theory oversees America’s 18 spy agencies) but has an inconvenient history of criticizing America’s military adventurism in general and its bullying of Venezuela for oil in particular.

Her spy colleague John Ratcliffe, director of the CIA, seems happy just to be in the room when things happen. So is Secretary of “War” (Defense, really) Pete Hegseth, who has little to say about grand strategy, concentrating instead on building a brand around “lethality” for its own sake.

The understated, professional and convincing embodiment of America’s martial prowess is instead Dan “Razin” Caine, the chairman of the joint chiefs, and by all appearances Trump’s favorite. It falls to Caine — after the bombing of Iran, say, or this Venezuelan operation — to narrate the military aspects, which he does in a politically neutral but engrossing style made for Netflix. His sway only extends to tactics, though, not strategy.

At the strategic level, Trump is flanked by two men who would in normal times be ideologically opposed, and who have both the intellectual heft and the ambition to run for president: JD Vance, the vice president, and Marco Rubio, who wears many hats, including those of national security advisor and secretary of state, and now apparently also Venezuelan viceroy.

Vance represents the isolationist wing of MAGA — he expressed concerns about bombing the Houthis in Yemen, for instance — but swings behind anything that Trump does because he knows what’s good for him. Notably, he was not lined up behind Trump during the press conference after the Venezuelan coup.

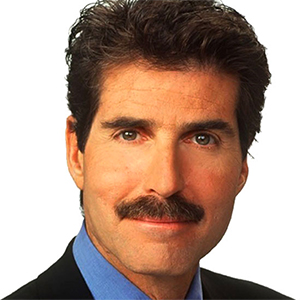

The man of the hour is instead Rubio. The son of anti-communist Cuban emigres, he has for years railed against the regimes in Havana and Caracas. (The Venezuelans allegedly even hatched an assassination plot against him once.) Superficially, he might seem to be driving Trump’s hemispheric activism. That impression overlooks his own trajectory as a politician, though.

It’s worth revisiting the old Rubio, as in this speech he gave as a senator during the Obama administration. That Rubio was a traditional Republican hawk in the Reagan mold, fired by a belief in America’s might but also its exceptionalism and moral purpose — “the torch” it must hold to the world as its “beacon.”

The old Rubio stood for free trade and strong alliances, for hard but also soft power as wielded by the U.S. Agency for International Development (whose dismantling he has overseen for Trump). He stood for liberty, democracy and human rights and against tyranny and autocracy, not just in Caracas but also in Moscow and Beijing.

His oratory was idealistic: “Our legacy is a crumbled wall in Berlin,” he said in 2013. “It’s the millions of Afghan children — including many girls — now able to attend school for the first time. It’s vibrant democracies and steadfast allies such as Germany, Japan and South Korea.” His worldview was also explicitly globalist: “Our foreign policy cannot be one that picks and chooses which regions to pay attention to and which to ignore.”

That Rubio of yore, in short, was almost the exact opposite of the Rubio on display now, as consigliere to a president who wields tariffs with abandon, restricts visas, disdains allies, coddles tyrants, laughs at soft power and sneers at international law and the rules-based order that America once built.

This new Rubio has honed impressive skills in keeping an immovable face for the camera when seated or standing behind a boss who is ad-libbing in the diplomatic style of Genghis Khan. It’s also this Rubio who then goes forth to articulate why Trump’s latest whims and contradictions are anything but whimsical or contradictory if only you listen to him, Rubio, without interrupting.

On the day after Maduro’s capture, Rubio overwhelmed successive television hosts with high-pitched verbiage. Taking umbrage at those “fixating” on the verb in Trump’s promise “to run” Venezuela, he lectured one interviewer that “what we are running is the direction that this is going to move moving forward, and that is we have leverage.” He clarified to another that “it’s not running the — it’s running policy, the policy with regards to this. We want Venezuela to move in a certain direction.” Dismissing the quizzical looks, he insisted that “it’s very simple.”

Rubio’s role is to convince America and the world, no matter what Trump has just said or done, that there’s nothing to see here. It’s all legal, it’s all sane, and even that talk about annexing Greenland is really about buying it, not invading. No matter how long Rubio talks, nobody is any the wiser as to Trump’s intentions.

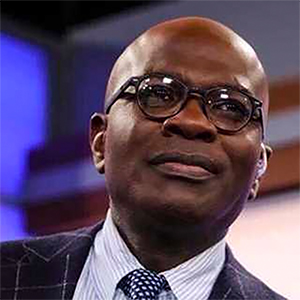

That makes another member of the administration so interesting. Stephen Miller is a MAGA firebrand who in his formal capacity, as deputy chief of staff and homeland security adviser, shouldn’t play any role in foreign policy. But he does, and he has Trump’s ear, if not his amygdala.

Just after the Venezuelan extraction, Miller’s wife, who is not in the administration, posted a map of Greenland dressed in the stars and stripes, with the caption “SOON.” Rather than qualifying her freelancing, Miller doubled down.

“We live in a world in which you can talk all you want about international niceties and everything else, but we live in a world, in the real world,” he lectured his interviewer, channeling his inner Thucydides. This is a world that is “governed by strength, that is governed by force, that is governed by power.”

And there you have it, Trumpism on the couch. If Rubio is the president’s Superego, Miller is his Id, and American foreign policy is the complex. “It was dark and it was deadly,” Trump said in describing the attack on Caracas. And so it will be again and again; here, there and elsewhere; for at least three more years.

_____

This column reflects the personal views of the author and does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Andreas Kluth is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering U.S. diplomacy, national security and geopolitics. Previously, he was editor-in-chief of Handelsblatt Global and a writer for the Economist.

_____

©2026 Bloomberg L.P. Visit bloomberg.com/opinion. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments