Michael Hiltzik: How Amazon provides a marketplace for worthless stem cell supplements

Published in Business News

I'll say this for the promoters of bogus stem cell treatments: They are terrific at finding new ways to market their goods and services.

For example, we've seen the proliferation of clinics offering purported stem cell-based cures or treatments for conditions including Alzheimer's, arthritis, cancer, macular degeneration, Crohn's disease, Parkinson's and even erectile dysfunction.

The Food and Drug Administration has said no scientifically validated evidence supports any of those claims, and warned the public against stem cell-related "unscrupulous hype" — in an advisory that seems no longer to be on the agency's website.

We've seen stem cell hype regurgitated by otherwise respectable news organizations, abetted by high-profile athletes attesting to miracle cures of their musculoskeletal ailments.

Now the marketers of dietary supplements have entered the field by attaching stem cell-related claims to the ads and promotions for their products. A leading venue for these direct-to-consumer pitches: the massive online reach of Amazon.com, where hundreds of these products are hawked.

That's the finding of a just-published paper by Canadian researchers who compiled a database of 184 stem cell supplement listings sold by 133 companies on Amazon's website. Their work attests not only to the extraordinary reach of stem cell-related marketing, but also to how supplement distributors fashion their promotions to stay within the admittedly weak oversight imposed on the industry by U.S. and Canadian regulators.

The advertising and promotional material "often distorts, exaggerates, and manipulates scientific evidence and rhetoric to sell stem-cell products, therapies, and ideas," the paper states.

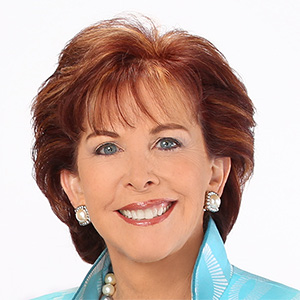

"What's happening is the use of the language of real science to sell their products," says Timothy Caulfield of the University of Alberta, a veteran debunker of pseudoscience and a co-author of the new paper. "You take an area of science that has gotten a lot of media coverage and taken a foothold in culture, and you use that language to give your product a veneer of legitimacy."

Adds biologist Paul Knoepfler, a stem cell researcher at the University of California-Davis, "I don't know if there's anything 'stem cell' about them. The stem cell stuff is just a marketing thing." Knoepfler posted a deep dive last year on his laboratory website about stem cell supplement claims. "In my view, stem cell supplements are not worth the money. They probably won't do anything too helpful specifically to stem cells and could have risks."

Amazon isn't the only marketplace where these products can be found — other e-commerce sites also offer them, and even some drugstore chains have them in their inventories. But Amazon dominates the online space.

Amazon told me that the supplements are marketed by independent third-party sellers who use Amazon.com as a platform. The company says it requires the sellers to follow the law, and that the supplements they sell meet the FDA's marketing rules, which as we'll see are the lowest of low bars. Amazon says it bars supplements that claim to treat or cure specific diseases, but those claims are banned by the FDA too.

In the U.S., supplement makers and distributors have had a friend in federal law for more than 30 years: the Dietary Supplement Health and Safety Act of 1994, known as DSHEA (pronounced "D-shay").

The brainchild of the late Sen. Orrin Hatch, R-Utah, and former Sen. Tom Harkin, D-Iowa, DSHEA effectively gutted government oversight of the supplements industry by hamstringing its regulation by the FDA. Both legislators were responding to the interests of commercial patrons — supplement firms were thick on the ground in Hatch's home state, and the supplement firm Herbalife was among the top campaign contributors to Harkin.

DSHEA turbocharged the growth of the supplements industry, which has expanded from a few billion dollars in value in 1994 to more than $200 billion today, and from about 4,000 products to more than 100,000 over the same period.

With the industry's greater wealth has come greater political heft, allowing it to beat back several attempts to tighten regulations under DSHEA. Those included a 2010 effort by the late Sen. John McCain (R-Ariz.) to enact a law mandating reports on illnesses associated with supplement use.

DSHEA essentially requires the FDA to assume that dietary supplements are safe until proved otherwise, at which point it's often too late to stem the toll of injury and death among their users. DSHEA is the source of what has often been called the "quack Miranda warning." You've probably seen it on websites or labels from businesses hawking supplements or treatments that have no known grounding in science.

Typically found in the small print of promotional material for supplements that claim generic benefits for the products, the legally mandated disclaimer says: "These statements have not been evaluated by the Food and Drug Administration. This product is not intended to diagnose, treat, cure or prevent any disease."

As the physician Peter Lipson, an assiduous pursuer of bogus medical claims, observed back in 2009, "DSHEA, as it was written and as it was intended, facilitates the legal marketing of quackery." When the FDA comes calling to say, "You're illegally marketing cures for disease," the businesses can respond, "No, we're not — it says right here that we're not curing anything."

Under previous administrations, the FDA provided consumers with stern warnings about taking stem cell promoters' claims at face value. Some of those warnings have disappeared from the FDA website. I asked the Department of Health and Human Services if they've just been moved elsewhere, or if the FDA is complying with the position of its Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr., expressed in an October 2024 tweet, that the FDA conducted a "war on public health" through its "aggressive suppression" of dubious therapies including stem cells. I didn't receive a reply.

Rather than make direct claims about cures, supplement promoters resort to vague boasts about their products using what the Canadian researchers identify as weasel words that can foster the impression of efficacy. They generally don't mention life-threatening diseases such as cancer or conditions such as dementia. Nor do they use "direct causal language of effect (e.g., 'mitigate,' 'prevent,' 'cure,' or 'treat')," the paper observes.

"The marketing can skirt these issues by mentioning that they can address 'brain fog,' or 'memory issues' or 'anti-aging,'" Alessandro Marcon, the paper's lead author, says. "They don't have to mention the word 'dementia,' which can trigger the regulatory bodies. But when people talk about 'brain fog' or 'lack of clarity' or lack of mental strength and memory, people are thinking about aging and having memory issues and having dementia basically."

The promotions often use hedging language, such as stating their products "may be helpful" or have "immune boosting" qualities. "The regulations almost provide a template for these companies to market their products, by giving them guidelines that say 'you can't say this, but if you say it in this way, it's acceptable.'"

The researchers found that among the most common benefits claimed for the stem cell products were "anti-aging" effects, enhanced immunity or energy, and brain-related improvements such as improved cognitive function, or more effective healing. Typically they didn't claim to provide stem cells themselves.

"There's a scientific implausibility of having human stem cells be in any of these products," Marcon says. "They're selling the idea that they allow your body to create more stem cells or to improve the functioning of the stem cells in your body, all of which is either not scientifically supported or there's no robust evidence to suggest that any of these products are capable of doing that."

"The data are just not there," Knoepfler says.

Consider the pitch by Henderson, Nev.-based Stem Cell Worx, which sells several products on Amazon, where it identifies itself as "the leader in stem cell supplements." Its products, like other "stem cell" products on the website, don't actually contain stem cells. Its "Stem Cell Worx intraoral spray"— a 3.5-ounce spray bottle costing $65, or $18.57 per ounce — consists of bovine colostrum, a component of cow's milk taken after the animal calves; the plant derivative resveratrol; and fucoidan, a seaweed derivative.

The company tells users the product can "activate your own adult stem cells" and "super charges" the "immune system." The company's co-founder, Maree Day, told me that it could produce clinical trial results validating these claims, but the studies she referred me to were mostly devoted to establishing that oral sprays under the tongue were better at delivering the formulation than pills or capsules.

A graph Day provided purported to demonstrate that "the Stem Cell Worx formulation produces steady percentages of bone marrow stem cell proliferation" and attributed that finding to "independent Scientists and Bio-Chemists" unaffiliated with her company, but didn't name them. Day declined to identify the independent lab that performed the studies, but she said "we have got all the clinical papers and everything."

As I've reported in the past, the targets of these sorts of promotions are consumers who are either looking for alternative treatments for persistent conditions or are dealing with chronic, incurable or terminal illness. Under previous administrations, the FDA tried to rein in the claims of stem cell promoters, but it may be backing off at the behest of RFK Jr.

Yet, the agency's previous advice, based on the doubts of credible scientists about promoters' claims for these products — and also apparently disappeared from its website — is still the best course for consumers and patients. What it used to say was this: "Don't believe the hype."

©2025 Los Angeles Times. Visit at latimes.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments