Spending law unenforceable if the president wants to violate it

Published in Political News

WASHINGTON — When the books close on the current partial government shutdown — on pace to break the length record later this week — congressional investigators will look for violations of the century-and-a-half-old law mandating that agencies cease any unfunded operations during an appropriations lapse.

But therein lies the rub: There’s no mechanism for enforcement of the law other than the discretion of the executive branch, and in this case the direction to possibly violate the law has come directly from the top — President Donald Trump himself.

The Government Accountability Office, charged with monitoring compliance with the 1870 law known as the Antideficiency Act, is still shut down due to the absence of appropriations. When the government reopens, the nonpartisan agency is likely to have its hands full reviewing the actions of an administration that’s taken more liberties with Congress’ Article I power of the purse than perhaps any other.

The most obvious culprit may be the Pentagon’s shift of unobligated funds in research and development, procurement and housing accounts to instead ensure the troops didn’t miss two paychecks last month.

Democratic-leaning legal minds argue that was an unprecedented violation of both the Antidefiency Act and the related “purpose statute,” which dates back to 1809, requiring that appropriations only be used for their stated purpose. “Anything less would render congressional control largely meaningless,” the GAO says.

The Trump administration, of course, argues that pulling from other accounts to pay the troops is consistent with both the purpose statute and the Antideficiency Act.

Trump wrote in his memorandum announcing the first tranche of payments in October that funds identified meet the “reasonable, logical relationship” to pay and benefits test under the purpose statute.

And the fact that the money being used comes out of multiyear appropriations that remain available in fiscal 2026 means the maneuvers comply with the Antideficiency Act, the administration argues.

Administrative and criminal penalties

The GAO typically adheres to a strict interpretation of the law. But despite its long-established place in federal appropriations law, the purpose statute appears to be relatively toothless.

Not so for the Antideficiency Act, which carries administrative as well as criminal penalties for violations.

Agency officials found to have violated the law are subject to “appropriate administrative discipline including, when circumstances warrant, suspension from duty without pay or removal from office.”

And where officials are found guilty of “knowingly and willfully” violating the statute, they can be fined up to $5,000, imprisoned up to two years, or both.

The GAO may ultimately discover other related violations, like they did after the 2018-2019 shutdown — to date the record holder at 35 days.

Back then, for example, the agency found that the Agriculture Department had made early payments of food stamp benefits that were contrary to appropriations law. They did not use contingency funds, which GAO said would have been fine, and which have been the subject of a legal battle that culminated in Monday’s USDA decision to drain those reserves.

In another instance, the GAO rapped the Interior Department for using national park recreation fees to pay for trash collection and restroom sanitation — activities normally funded by appropriations that had lapsed. That was also deemed a purpose statute violation.

Slap on the wrist

But no criminal penalties have ever been levied under the law, legal experts say, and administrative disciplinary actions are few and far between. Most violations are inadvertent and involve the bureaucratic equivalent of a slap on the wrist and corrective action taken to credit the proper appropriations account, replenish funds and the like.

More importantly, all the GAO can do is identify violations and point them out. The executive branch has long held that the GAO, as an arm of Congress, cannot impose its will on federal agencies. The authority to enforce that law as well as others lies with the Justice Department and other executive branch agencies.

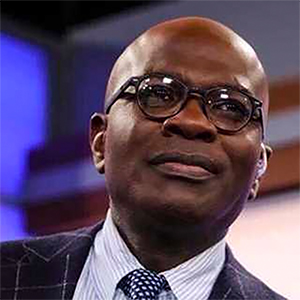

If administration officials interpret their own actions as legal, they won’t prescribe administrative penalties or prosecute alleged lawbreaking. Trump and Office of Management and Budget Director Russ Vought both contend the actions are legal, for instance, making it highly unlikely the Justice Department would choose to, say, prosecute Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth for paying the troops.

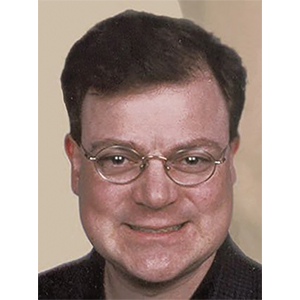

“The two remedies the act sets out, criminal prosecution and adverse personnel action, both depend on action by agencies that the White House is keeping under strict political control,” said David Super, an expert on administrative, constitutional and budget law at Georgetown Law School who has served as general counsel for the left-leaning Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

Legal experts said it’s untested whether a lawsuit against the administration for violating the Antideficiency Act would succeed. Super’s “best guess” is that the Supreme Court “would look skeptically on private efforts to enforce the act through litigation.”

And the only lawsuit that comes close — concerning the administration’s attempted firing of thousands of federal workers — is unlikely to provide much guidance.

The American Federation of Government Employees and several other unions sued the OMB and Office of Personnel Management on Sept. 30 over anticipated “reductions in force,” or firings of federal workers, during the shutdown.

The White House has put those plans on hold in compliance with a temporary restraining order issued in the case by U.S. District Judge Susan Illston in San Francisco.

No matter how the lawsuit is resolved, it might not shed light on enforcing the Antideficiency Act. The lawsuit accuses the administration of violating the act, on the grounds that it would have to spend money that Congress never appropriated to implement the layoffs.

But the unions’ claims were brought under the Administrative Procedure Act, a separate law. Super said he doubts the AFGE case “will tell us anything about whether the Antideficiency Act is privately enforceable, whether it succeeds or fails.”

To file a suit over the Antideficiency Act, a plaintiff would need standing. For example, federal employees could argue they were affected or targeted by the law. Even if the Supreme Court agreed there was standing, the harder test would be whether the plaintiffs had a “private right of action” to enforce the law.

Without that, the employees might get, at most, an order saying they could refuse to make improper payments, but not an order banning the government from making those payments.

As for whether Congress could sue, Super said the Supreme Court has generally found that Congress has not sustained the kind of injury that gives it standing to sue the executive branch. Instead, the court has said Congress can defend its prerogatives through other means.

“Unfortunately, the most common other means is withholding appropriations, which does not work if the administration is willing to spend money without valid appropriations,” he said.

Statute of limitations

Even if the Trump administration does not enforce the law to the satisfaction of critics, it’s possible the next administration could, since there is a five-year statute of limitations for federal crimes. But history would suggest that a retroactive enforcement is unlikely to happen.

After Joe Biden was elected president, no prosecutions of the GAO-alleged violations during the 2018-2019 shutdown followed.

Super said that precedent “is indeed instructive. The Biden administration took office in plenty of time to prosecute ... violations but, to the best of my knowledge, made no attempt to do so.”

Super added, though, that in his view those violations were not “nearly as egregious as the ones we are seeing now. So it may not be a perfect precedent.”

©2025 CQ-Roll Call, Inc., All Rights Reserved. Visit cqrollcall.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments